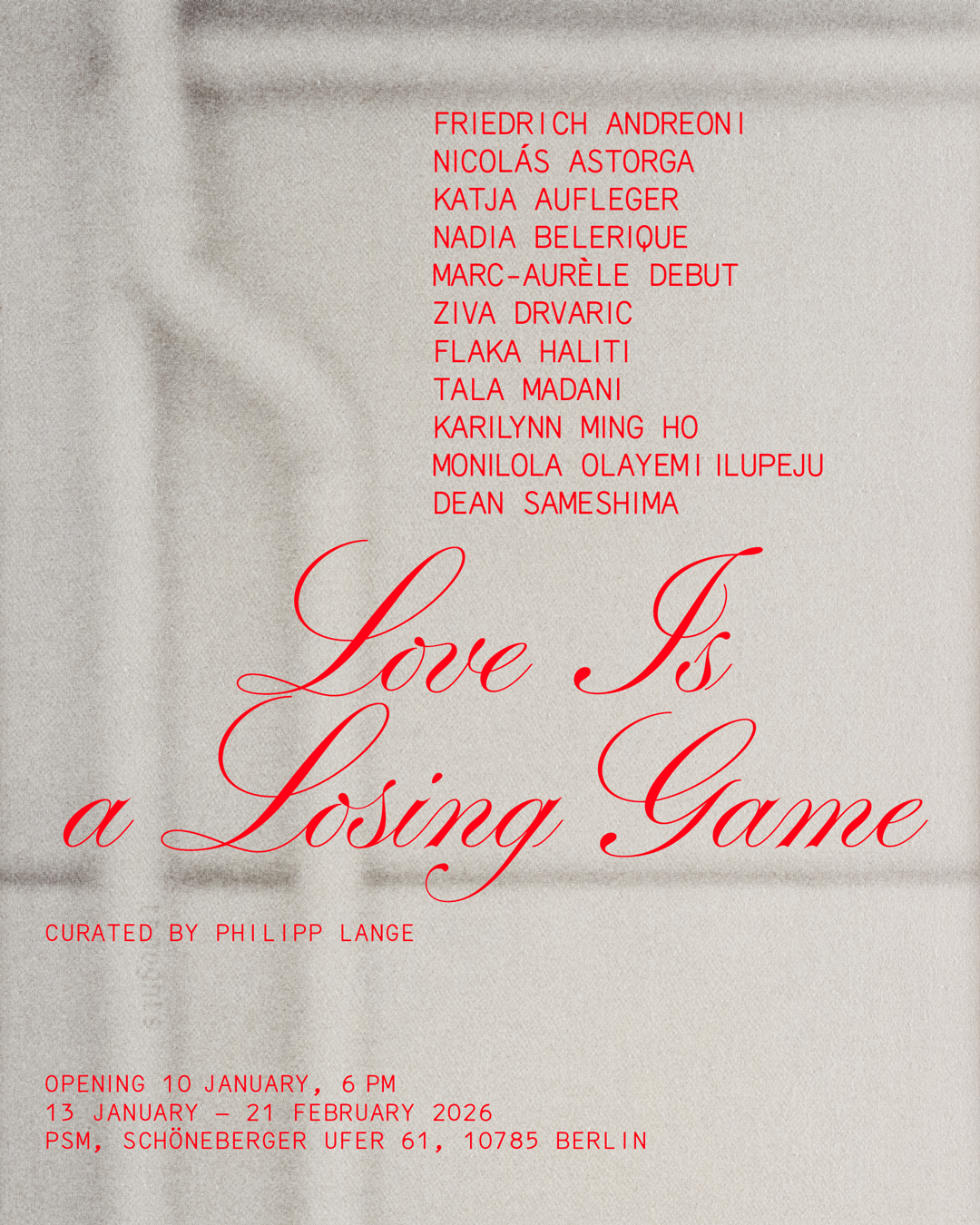

Love Is a Losing Game

11.01. – 21.02.2026

with works by

Friedrich Andreoni, Nicolás Astorga, Katja Aufleger, Nadia Belerique, Marc-Aurèle Debut, Ziva Drvaric, Flaka Haliti, Tala Madani, Karilynn Ming Ho, Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju, Dean Sameshima

curated by Philipp Lange

Dear Amy,

Instead of an exhibition text following a familiar model, which would likely resemble a typical press release, I would like to address my thoughts on mediating this exhibition directly to you. The exhibition owes its, in my view, beautiful title to you: Love Is a Losing Game. Your song of the same name was released with your album Back to Black in 2006 and thus celebrates its 20th anniversary this year – even though you only released it as a single the following year and turned it into a global success. Sadly, it was your final release during your lifetime, part of an impressive artistic body of work that continues to resonate today and will do so forever.

As is customary in love songs, the subjective experiences you articulated as the songwriter also play a central role in your piece. Your words reveal memories of pain; the lines point to lived confrontations with loneliness, disappointment, and transience – feelings we inevitably associate with love. Yet you do not place yourself in the role of a victim of a failed relationship, on the contrary: in the deliberate statement that love is a game in which there are only losers, I see a moment of self-empowerment. For in consciously accepting failure lies an act of appropriation and strength, a reclaiming of agency over one’s own disastrous situation. At the same time, your statement remains debatable, one that creates friction. And this is precisely where a fundamental quality of love lies: it is defined by pluralistic perspectives, can never be conclusively determined, never grasped in its entirety, nor ever fully understood. We all ascribe different qualities to it, shaped by our individual experiences, in a process that is never complete. As an ambivalent assertion, Love Is a Losing Game – like love itself – eludes a clear definition. This is precisely what forms the basis of this group exhibition. It brings eleven additional artists to your side, each contributing their own, very different perspectives on the theme of love, sometimes more overtly, sometimes less. The exhibition does not use your words to frame all the works within it, nor to prove or refute your legitimate statement. Rather, it lays open various lines of thought, places them alongside one another as equals, and thus raises more questions than it offers answers about this strange phenomenon called love.

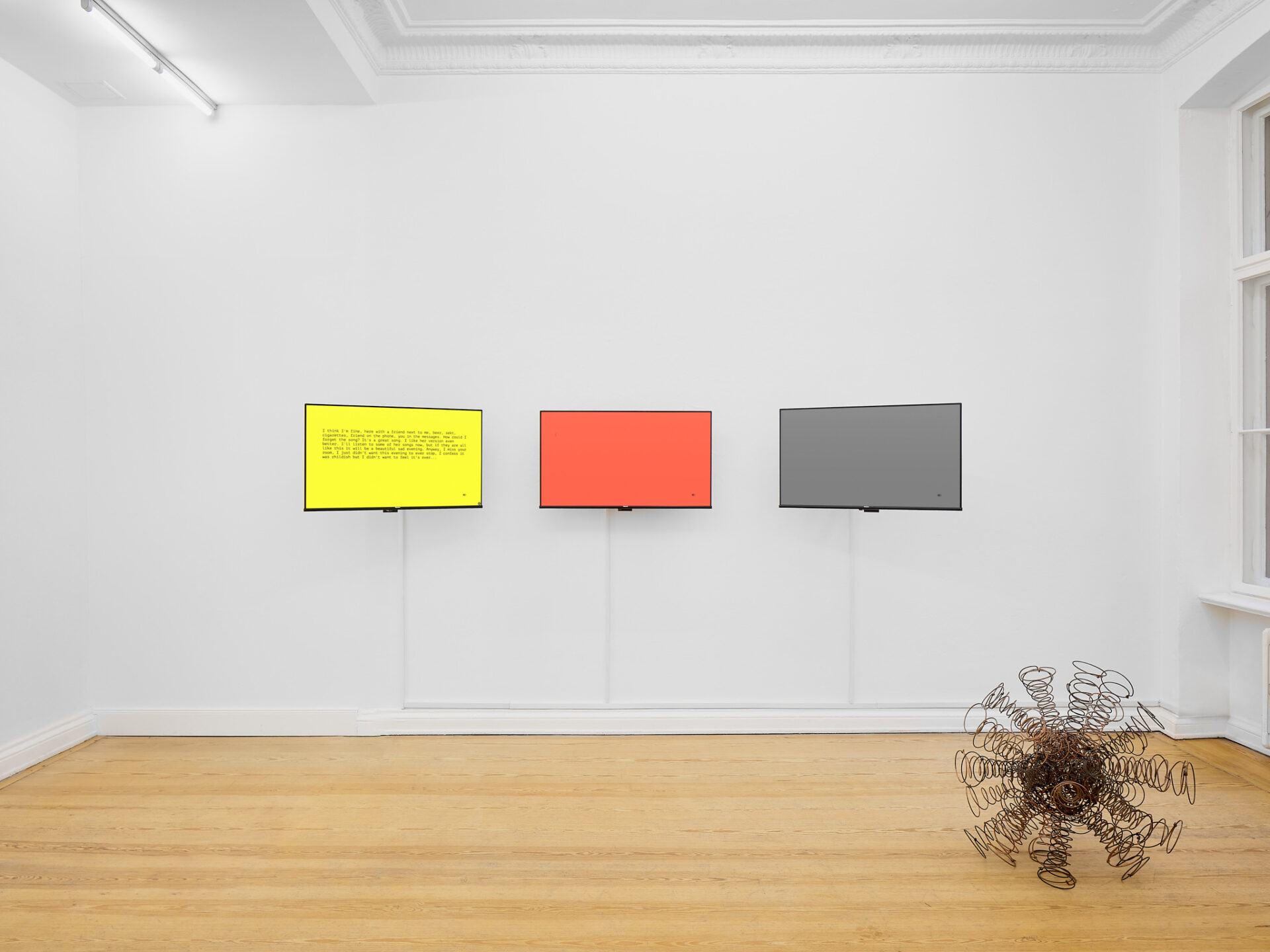

Your 20-year-old song also sets the rough timeframe within which we move – both with regard to the years in which the selected artistic works were created and in light of digital developments from then until today: technological advances that strongly influence our (relationship) behavior. Tala Madani’s The Dancer (2010) forms a choreographic opening: in the video, a lonely man dances with passion and skill, as if he wants to impress the viewers. Known for paintings and installations that reflect the complexity and contradictions of life, the artist depicts human figures in vulnerable, unsettling, and at the same time humorous states, often staging her protagonists in dreamlike locations within a partially disturbing atmosphere. Flaka Haliti, in I Miss You, I Miss You, Till I Don’t Miss You Anymore (2012–2014), turns to digital communication in (long-distance) relationships. She examined digital love

letters, as they were typically sent via email before social media and messaging apps, combining individual fragments into new, semi-fictional texts. Her analysis results in three chapters: the infatuation phase (yellow), the passionate peak phase (red), and the final phase, in which replies are delayed and a growing distance between two individuals becomes palpable (gray). The artificially generated voice-over allows us to perceive, from a detached and alienated position, how the written word is often interpreted in absurdly emotionally charged ways when we are wearing rose-colored glasses.

It is no coincidence that numerous video works are gathered in the exhibition, as a large part of our everyday lives today – our communication and even partner-seeking – takes place on screens. Katja Aufleger’s I’M ANGRY JUST NOT SURE ABOUT WHAT (2021), for instance, is shown on a smartphone that could itself have served as the camera for this video. We see dandelions being set alight by hand, their blazing ignition and, shortly thereafter, their extinction. Although the artist abruptly ends life in this radical act, the endless repetition suggests that there is no escape from the cycle. The work may also symbolize a certain madness, but equally the desire we can feel when caught in the midst of emotional chaos.

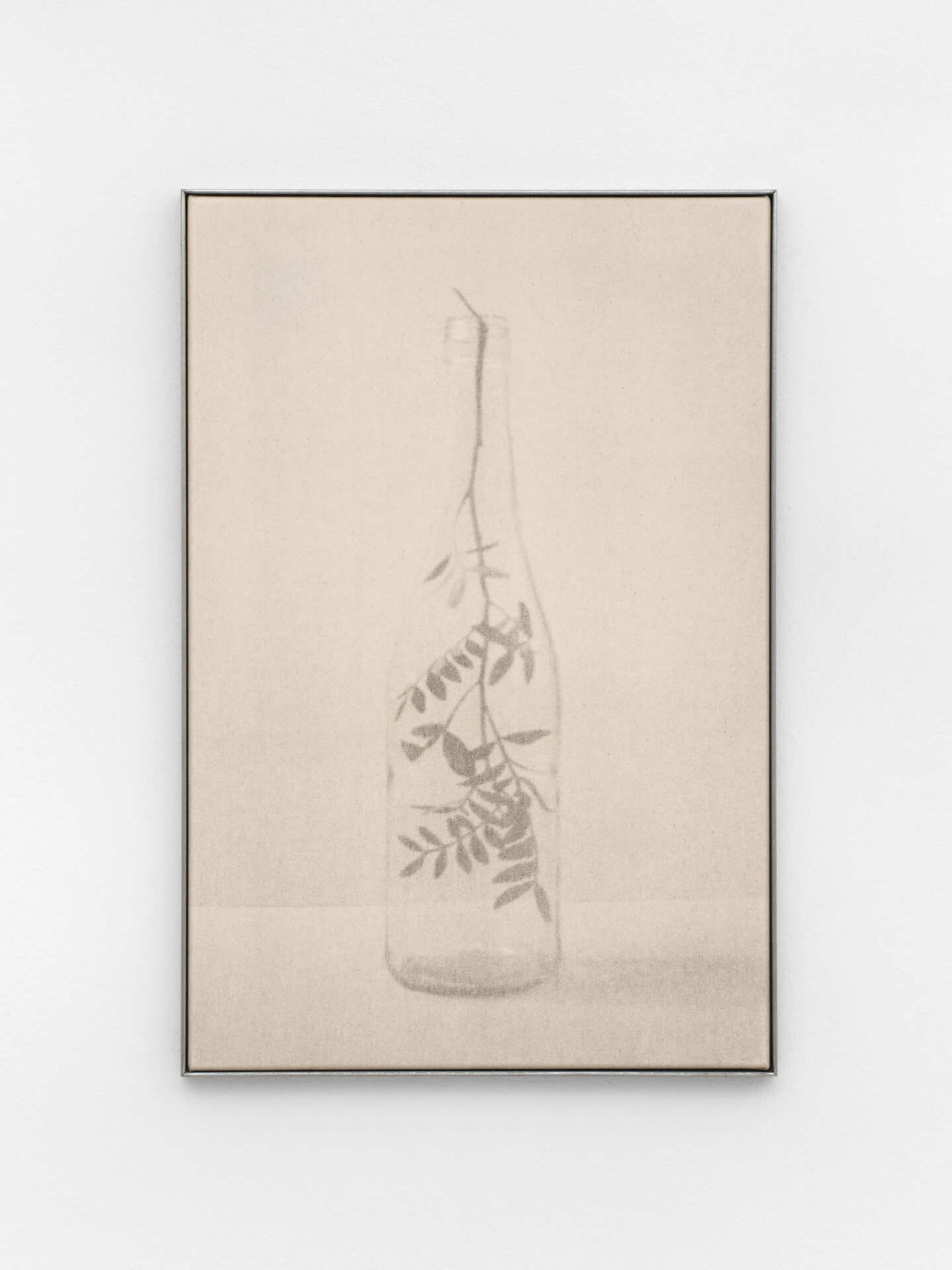

Even though the selected works in the exhibition rarely depict the human body directly, bodily experience nonetheless plays a central role. Nicolás Astorga presents There’s a stone in my chest (2024–2026), a heart pierced by arrows. Referencing Saint Sebastian, the wall sculpture visualizes a feeling of heaviness and pain. The mineral coal stone was found by the artist already in the shape of a heart and lovingly fitted with steel arrows. Elsewhere, Cupid seems to have struck: a Cockring (2020) is fixed to the wall by another arrow that might just have been shot through the window. Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju presents moments of masturbation in drawings from her ongoing Body Print Series, for which she used charcoal on paper during self-pleasure (Masturbation Studies 1–5, 2022). Her orgasm(s) is/are traced as an abstract-expressionist rendering on the partially torn sheets, while self- love receives a special form of appreciation through classical framing with a passe-partout. Friedrich Andreoni, in Two figures and one anchor point series (2024), tells of the endless constellations that two bodies can enter into with one another. On each sheet of the series, two nearly identical forms are drawn, engaging in a relationship with each other in constantly shifting ways and searching for their shared point of stability. Hanging freely along the gallery’s long corridor, they appear suspended in a state of levitation, as if they might find one another like in a game of Tetris or lift upward in free motion. Ziva Drvaric, in turn, visualizes inner emotional states in poetically inflected screen prints on natural linen as well as in installations made of everyday objects. In Inward II (2026), a eucalyptus branch unfolds inside an empty bottle, seemingly stuck in a hopeless situation. In Thoughts (2023), two bodies – here, two pipes – nestle against each other only to separate again shortly thereafter. In To and From (2025), two light bulbs share warm light in a balanced interplay. With a sensitive eye for what surrounds us, these works speak of situations of togetherness and isolation.

Through the abstract representation of corporeality, visitors are thrown back onto their own physicality within the exhibition space. They find themselves not only in a gallery, but also in a former apartment into which the exhibition space is embedded. This domestic aspect played a role in the selection of certain works, as my aim was to reflect the individual within their own four walls – at a place where bodily experiences, emotions, and perceptions of love condense in a particular way, whether through cohabitation with a partner, the experience of heartbreak, or the handing over of a second apartment key as a defining moment in the course of a relationship. Thus, BETWEEN US (2020) by Katja Aufleger – her own key ring – is located directly next to the entrance door. One of the keys is opposed by an exact puzzle piece. This supposedly ideal counterpart, however, cannot open any lock; it serves no function. Does the perfect match even exist? With her two works, Katja Aufleger assembles objects we carry close to our bodies: phone, lighter, keys. A reminder to remain mindful of what we carry with us – and never to rely entirely on others.

The kinetic installation How Long Is Your Winter Part 2 (2026) by Nadia Belerique extends site- specifically across the window wall of the first room, making it the first visible – yet perceptible only upon second glance – work of the exhibition. Motorized blinds block the view outside as they open and close in an opaque choreography, creating intermediate spaces that lead to shifts in perspective and changes in light or even emotional atmosphere. With closing as a gesture of withdrawal, the

separation of inside and outside, and winter as a metaphor, the artist opens up a wide field of interpretation. Marc-Aurèle Debut, in his new body of work, engages with the emotional charge embedded in domestic materials –

particularly those associated with rest, intimacy, and care. Reused beds, upholstered furniture, and coil springs function as silent witnesses to bodies and relationships over time. Allowing (2026) focuses on a moment of emotional learning and vulnerability, using the form of a mattress to sustain tension between attachment and letting go. Marked with the constellation of two zodiac signs, the artist dedicates this work to his first relationship, in which he allowed himself to have feelings for that person. The sculptural works of the series Aliveness (2026) are composed of springs from discarded mattresses and can move through space like tumbleweeds across the desert. His works understand love and feeling as active, mutable states. Rather than seeking resolution or closure, they explore how emotional openness persists through contact, change, and time. The Intervals (2026) by Dean Sameshima presents a fragmentary assemblage of movie tickets from Berlin porn cinemas and cruising locations near the gallery. The artist began collecting these 24-hour passes in 2015; they mark precise dates and specific moments. Over a period of ten years, they formed temporal traces into an ensemble of twelve works, in which the tickets – partly mixed with similar cards from Los Angeles – are assembled into grid-like structures. The images were screen-printed onto aluminum-framed mesh, emphasizing both their materiality and their origin in reproduction. While visiting these places can be read as a search for closeness, the act of collecting the tickets simultaneously reveals a moment of holding on to lived memories.

Finally, Love Is Just a Four Letter Word (2014) by Karilynn Ming Ho forms a kind of extended footnote as the exhibition’s final work. Laden with theoretical references to Walter Benjamin and George Howard Darwin, the short film addresses how love songs in popular culture, through representations of desire and loss, sustainably shape our perception of love. “The pop song is the ultimate capitalist device, it is a system that keeps us desiring and dreaming for a love beyond our own immanence,” the video states. According to the artist, “the market produces desiring bodies capitalizing on an economy of emotions, projecting a ‘love’ that is insatiable, unattainable, and ultimately an illusion – a desire that can never be fulfilled, keeping us wanting more.” I do not know whether answers to the big questions about love can be found through this exhibition. Perhaps Love Is a Losing Game instead reveals love’s impenetrability and its beauty, which can be found even in pain. Thank you for leaving us your song. I wish we could see this exhibition together.

With love, Philipp

Exhibition dates: January 11 – February 21, 2026

Open: Tuesday – Saturday 12 – 6 pm

German exhibition text | Floorplan

Various vinyl and fabric vertical blinds, motors, control panel, 5,50 x 3,35 m

Screen print on canvas, steel frame, 61 x 41 cm

Reclaimed bed and sofa springs, metal wire, 55 x 55 cm

Keychain of the artist, key, 30 x 9 x 4

Three-channel video + audio, 113′ loop

To and From, 2025 (left)

Two smart light bulbs, lamp holder, stainless steel, micro controller

24 x 24, variable height

and

Thoughts, 2023 (right)

Screen print on canvas, stainless steel frame 61 x 41 cm (framed)

Inkjet print on canvas 21 x 14 cm

each 25 x 25 cm

4K-Video, Farbe, Ton, 7’ Loop

Steel, silicone, dimensions variable, object: 85 x 85 x 5 cm

Linen, upholstery foam, mdf, wood, staples, 135 x 190 x 5 cm

Screen print on canvas, stainless steel frame, 28 x 22 cm (framed)

Charcoal and graphite on paper, 27.5 x 35 cm

One-channel video + audio

9′ 13“

Photos: Joe Clark